Greece has signed a new defense agreement with France to acquire 16 Exocet MM40 Block 3C anti-ship missiles, expanding a series of high-profile procurements aimed at transforming its armed forces and enhancing its maritime strike capabilities.

The deal, formalized in Athens between Greek Defense Minister Nikos Dendias and French Defense Minister Sébastien Lecornu, is part of a broader, decade-long military modernization plan valued at €25 billion (US$28.21 billion). This ambitious initiative reflects Greece’s pivot towards high-tech, networked warfare following years of underinvestment in defense during the economic crisis.

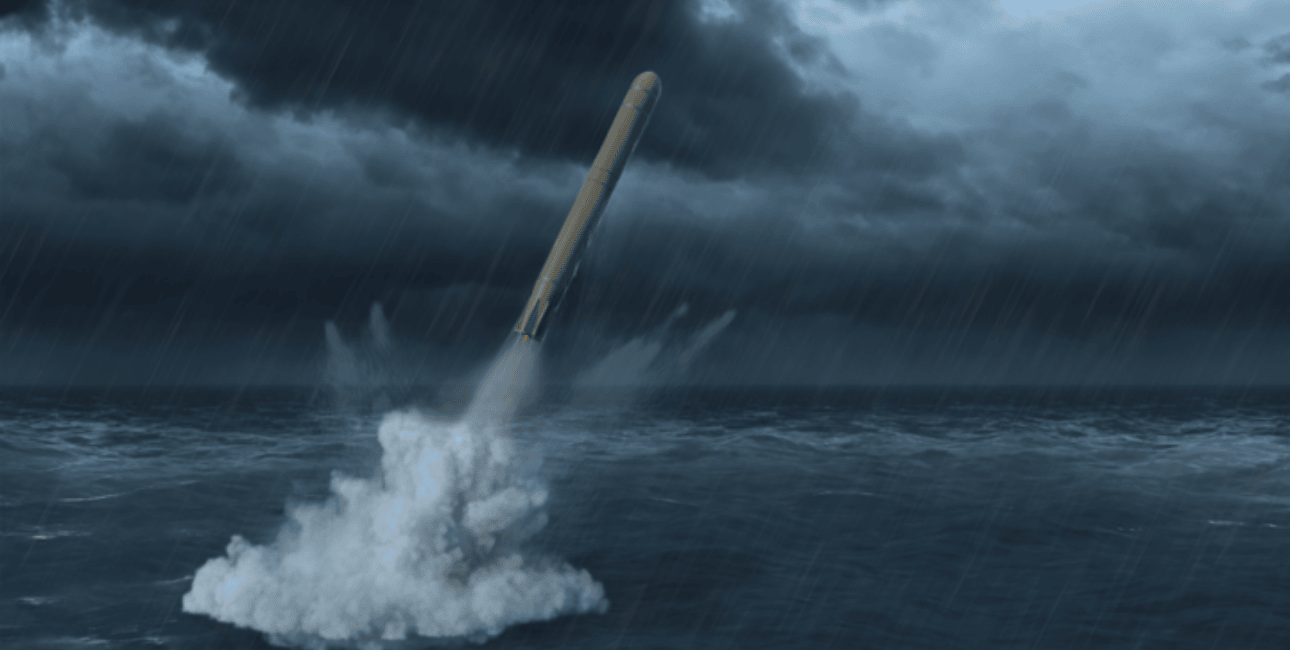

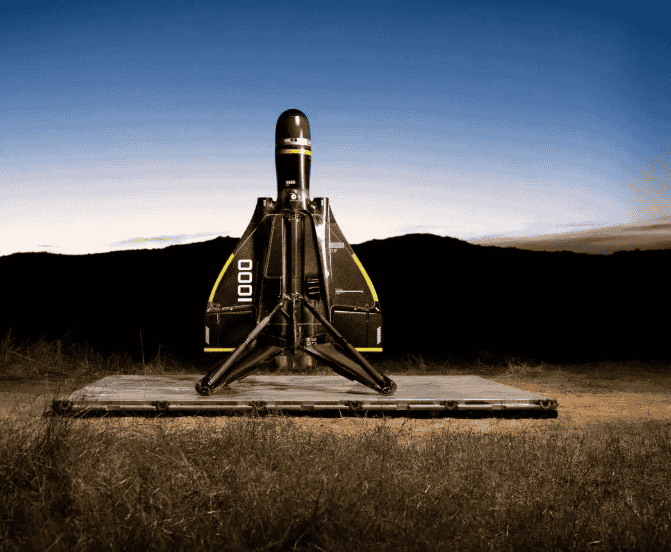

The Exocet missiles—developed by European arms manufacturer MBDA—are designed primarily for coastal defense and sea-denial operations.

With an operational range of around 200 kilometers and advanced sea-skimming capabilities, the Block 3C variant is optimized for precision strikes on moving naval targets.

This latest acquisition is regarded in Athens as a critical step toward establishing a more autonomous and technologically advanced defense posture, particularly in a region undergoing rapid and competitive militarization.

This development builds on earlier major procurements from France, including 24 Rafale fighter jets, three Belharra-class frigates, and NH-90 transport helicopters.

Negotiations are reportedly ongoing for a potential fourth frigate. These agreements are part of a steadily deepening Franco-Hellenic defense partnership, institutionalized by a landmark 2021 strategic agreement that includes a mutual defense clause—a rare provision among European Union member states.

During his visit, Lecornu also met with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, further emphasizing the strategic alignment between Athens and Paris. Notably, the agreement was announced without public disclosure of its financial value, in line with a recent pattern in Greece’s defense procurements where cost details have been withheld.

The BrahMos Factor & Greece’s Broader Pivot

India has taken steps to promote its BrahMos cruise missile to Greece as part of a broader effort to strengthen defense and security ties following Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s landmark visit to Athens in 2023.

In Greece, defense analysts and retired military officials have endorsed the potential acquisition of the Indo-Russian BrahMos missile system. Media commentaries and think tank publications have argued that BrahMos could offer Greece a decisive edge in contested maritime zones.

The Greek media has been making a strong case for acquiring the BrahMos anti-ship missile to bolster the country’s naval power in the entire geographical range between the Aegean, Crete, and Cyprus.

Earlier, the Greece City Times, in an article, wrote: “Equipping the Eastern Aegean islands with Brahmos land-sea arrays, combined with their long range and a short distance from the Asia Minor coastline, would mean minimal reaction time on the radars of Turkish naval ships, especially in conditions of missile saturation from mass firings from Greek Brahmos coastal defense arrays deployed on the Eastern Aegean islands.”

Two Greek academics had also stirred debate around the acquisition. Emmanuel Marios Economou and Nikos K. Kyriazis of the University of Thessaly advocated for acquiring the BrahMos cruise missile system. Economou and Kyriazis argue that the deployment of BrahMos on Greece’s eastern Aegean islands would create a “denial and prohibition of maritime access” for the Turkish Navy.

The supersonic cruise missile—jointly developed by India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and Russia’s NPO Mashinostroeniya—has already attracted global attention for its speed, precision, and adaptability.

Capable of reaching speeds up to Mach 3 and striking targets over 500 kilometers away, the BrahMos provides a range and velocity advantage over subsonic systems like the Exocet. Its low-altitude trajectory makes interception difficult, and its compatibility with air, sea, and land platforms enhances its operational flexibility—an appealing feature for a country like Greece facing complex maritime threats.

However, as of now, there is no formal agreement between Athens and New Delhi regarding a BrahMos purchase.

For Greece, procuring BrahMos would represent a potential break from its traditional defense sourcing strategy, which has long been centered around NATO interoperability.

Since BrahMos is a product of India-Russia collaboration, its integration could face compatibility challenges with existing NATO systems. Moreover, Greece’s political support for Ukraine amid the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict complicates any engagement with systems involving Russian technology.

From India’s standpoint, a BrahMos sale to Greece would be symbolically and strategically significant. It would mark India’s first defense export to a NATO member and signal the growing international appeal of its indigenous weapons platforms. Such a development would also align with India’s current push under Prime Minister Modi to become a global arms exporter, as seen in recent deals with countries like the Philippines.

Toward A New Military Doctrine

In a recent address to the Greek Parliament, Defense Minister Dendias outlined a new strategic vision that emphasizes a transition away from conventional defense systems toward a fully digitized and technologically advanced military.

This shift is not merely aspirational but grounded in necessity. Between 2010 and 2018, Greece’s armed forces experienced a prolonged period of underfunding due to the national debt crisis.

Many of its defense platforms became outdated, and logistical chains suffered. The current modernization drive aims to reverse these setbacks by investing in next-generation systems that can meet the demands of emerging warfare.

Although Turkish officials have refrained from publicly commenting on Greece’s latest defense procurements, regional analysts note that the timing of these acquisitions reflects deepening security concerns in Athens.

Despite being NATO partners, Greece and Turkey remain locked in long-standing disputes over maritime boundaries, airspace, and energy exploration rights. These disputes have repeatedly brought the two nations to the brink of armed confrontation over the past several decades.

Dendias has not explicitly framed Greece’s modernization as a reaction to Turkey. Yet his recent remark—“Greece does not threaten, but is threatened”—indicates how the Greek leadership views its evolving security environment in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Alongside its alignment with France, Greece is also expanding military cooperation with Israel and the United States. These partnerships include joint military exercises, intelligence-sharing frameworks, and defense technology transfers. Taken together, they form the basis of Athens’s effort to build a multi-layered security architecture that is not only reactive but also forward-looking.

Beyond operational concerns, Greece’s modernization is also tied to its strategic ambition to project greater autonomy within the EU and NATO.

By investing in diversified defense partnerships and acquiring advanced systems from a range of global suppliers, Greece signals its intention to play a more assertive role in regional security affairs—one that is not solely dependent on traditional Western defense frameworks.

While many of Greece’s recent procurement decisions are presented in technical terms, the broader geopolitical calculations are difficult to miss.

The Eastern Mediterranean remains a highly militarized and politically volatile theater.

The growing presence of regional and global powers, combined with unresolved boundary disputes and competing energy claims, has made deterrence a core tenet of Greece’s security policy.

Athens’ response to this evolving threat landscape is grounded in rapid technological adaptation.

Ultimately, Greece’s strategy is clear: maintain deterrence by achieving a technological edge, expanding strategic partnerships, and accelerating defense modernization. In an unpredictable and contested region, these pillars are viewed in Athens not only as a military imperative but also as a political necessity.

- Penned By: Mohd. Asif Khan, ET Desk

- Mail us at: editor (at) eurasiantimes.com