A week after Rome ratified the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) treaty, leaders from Japan, the UK, and Italy convened on November 19 to explore broadening the ambitious joint fighter aircraft development initiative to include additional international partners.

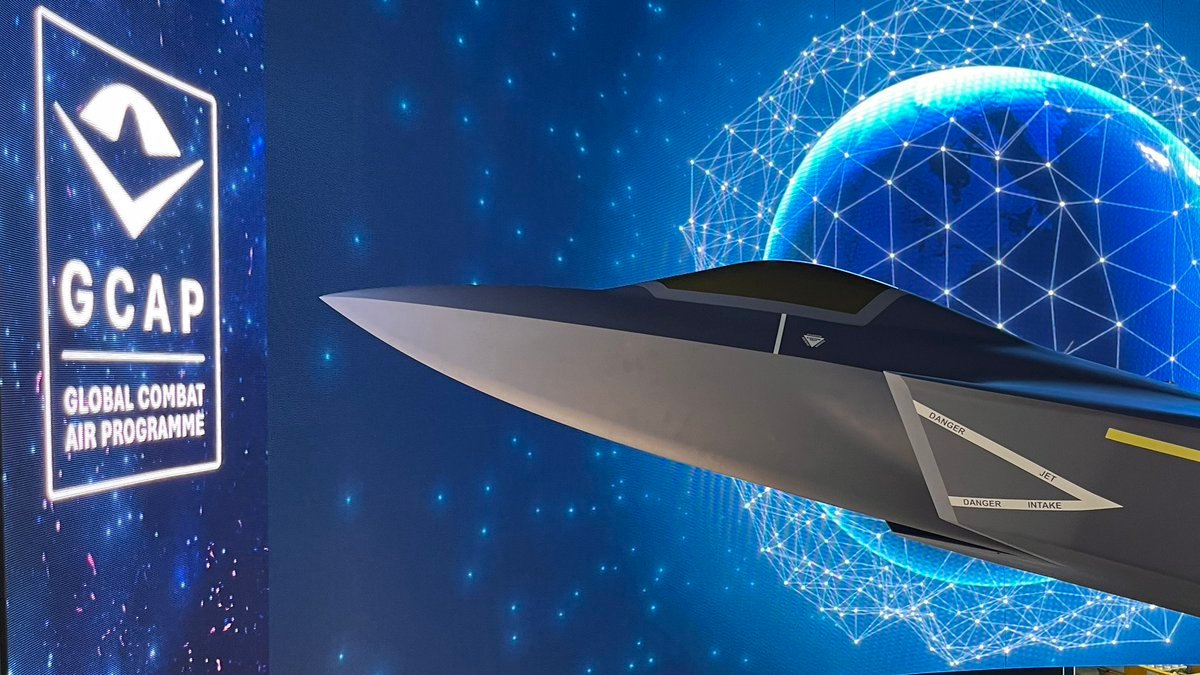

The GCAP, launched in 2022, is a collaborative initiative involving the UK, Japan, and Italy. The program aims to design, manufacture, and deliver a next-generation crewed combat aircraft.

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer underscored the need to expedite progress on the program while reiterating their dedication to enhancing the existing partnership.

The meeting took place on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro, marking a pivotal moment for the trilateral project.

“They agreed on the importance of the project continuing to move forward expeditiously, reaffirming their common intent to further strengthen the ongoing collaboration,” a joint statement noted.

British Prime Minister Starmer highlighted the trio’s “ambition to widen participation to a broader range of international partners in future.” However, details about potential new participants and their roles remain undisclosed.

The discussions follow the ratification of the GCAP treaty, which binds Italy, Japan, and Britain to the program and formalizes the creation of the GCAP International Government Organization (GIGO).

This entity will oversee the development of the next-generation fighter jet, setting capability requirements and managing the program’s industrial framework.

The treaty’s ratification has paved the way for the project’s next phase, with full development and design scheduled to begin in 2025. According to a November 20 joint statement, a joint venture agreement to establish a company for delivering the multibillion-dollar initiative is expected to be signed “soon. “

Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Italy’s Leonardo, and Britain’s BAE Systems will lead the project as system integrators. Given the complexity of building advanced fighter jets, the program will involve an intricate global supply chain.

Japanese Prime Minister Ishiba underscored GCAP’s strategic significance, describing it as “the cornerstone of broad cooperation among the three countries for decades to come.”

Meanwhile, the partners’ unified stance is expected to address concerns in the British media about potential disruptions stemming from the UK’s strategic defense review next year.

By fostering collaboration among key defense manufacturers and potentially welcoming new allies, GCAP aims to bolster the defense-industrial base of the three nations while advancing cutting-edge military capabilities.

Which Countries Could Join GCAP?

No further details about which nations might join the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) have been disclosed. Sweden, once a participant in the British-led initiative, formally withdrew by November 2023.

In November 2023, the Swedish government confirmed its decision: “Sweden confirms that involvement in Tempest is now officially dead. We walked away from tri-lateral studies with the UK and Italy about a year ago and launched a national study. I will not answer questions about why it didn’t work with the UK and FCAS.”

Following its withdrawal, Sweden has shifted its focus to exploring independent pathways for advancing its next-generation combat capabilities.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia has emerged as a potential candidate for the program, with its interest gaining traction throughout 2023. In a notable instance in March 2023, Saudi Arabia prematurely announced its participation in GCAP, a claim that was later retracted by the UK.

Despite the misstep, there have been indications of ongoing discussions. In September 2023, a British official expressed optimism about Saudi Arabia eventually joining the program, stating, “I think, from a UK point of view, the expectation, and the hope is that, that’s the direction that we will go in.”

However, the road to Saudi Arabia’s inclusion remains uncertain. Japan has reportedly opposed the Kingdom’s entry, underscoring the necessity of unanimous approval from the three existing members—Britain, Japan, and Italy—for any new participant.

The prospect of Saudi Arabia joining GCAP has also drawn attention to the broader dynamics of UK-Saudi relations. While some critics have raised concerns about Saudi Arabia’s human rights record, the UK has defended its decades-long defense ties with Riyadh.

In December 2023, then-UK Defense Secretary Grant Shapps highlighted the depth of this relationship, stating, “The UK holds a defense relationship with Saudi that is very deep and goes back many decades.”

Yet, localization remains a critical factor in any potential agreement. Saudi Arabia has maintained that it will not proceed with defense transactions unless they involve local production and development.

The Kingdom envisions contributing to GCAP through manufacturing, technological advancements, and skilled human capital. However, Saudi officials said their participation must be comprehensive and meaningful, stating, “Otherwise, it doesn’t make sense for us.”

While Saudi Arabia’s potential inclusion could bring substantial resources to GCAP, its integration hinges on navigating diplomatic sensitivities and meeting localization demands.

Germany has also previously emerged as an unexpected candidate for potential involvement in the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP).

In November 2023, the EurAsian Times reported that Germany might consider withdrawing from its commitment to the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), Europe’s other multinational sixth-generation fighter project, due to persistent disagreements with its primary partner, France.

The reported tensions between Berlin and Paris stem from differing priorities and visions for the FCAS program, which has faced numerous delays and funding disputes since its inception. This speculation has fueled discussions about Germany possibly exploring alternative avenues for advanced combat aircraft development, including the GCAP initiative.

However, German officials have since reaffirmed their commitment to FCAS and highlighted their intention to maintain collaboration with France on this ambitious initiative.

Yet, if Germany were to shift course and join GCAP, it would mark a transformative moment for the program. Germany’s entry could bring industrial capacity, advanced technology, and financial resources, majorly boosting GCAP’s development and enhancing its status as a premier sixth-generation fighter initiative.

Such a move could also influence other nations to consider joining, further broadening GCAP’s international reach. For now, Germany’s alignment remains firmly with FCAS.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom also previously invited India to collaborate on the Tempest program, the precursor to GCAP, but the prospects of India joining the initiative remain slim at present.

However, the slow progress of India’s fifth-generation fighter program could change the dynamics in the future, potentially leading to a reconsideration of the GCAP option.

In a similar line, Shashank S. Patel, an India-based geopolitical and defense analyst, told EurAsian Times that India’s most significant challenge lies in the successful domestic development of the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) before 2030.

With an urgent need to upgrade its air combat capabilities, India has been compelled to procure advanced fighter jets from foreign manufacturers, a factor that may affect its interest in pursuing participation in the GCAP initiative.

He said, “As the members of GCAP agreed to expansion, it is a certain possibility that India will get an invite to join this sixth-gen fighter jet program. India’s inclusion will shorten the time elapsed for completion of the project by some years compared to the planned launch in the mid-years of the next decade. It is not a baffling defense enigma that India is open to scrolling such proposals, as India-France held such talks in the past to materialize such joint development initiatives.”

Patel argued, “It is obviously in favor of Indian air capabilities to join such next-gen tech initiatives, which will enhance the current rolling of fifth-gen fighters as well as establish its own elite cohort of countries of sixth-gen fighters of the future. The core lies in ‘how early and when this multinational grouping develops supersonic 130kN+ thrust class engines to propel such jets’.

Another key factor that may influence India’s decision is the current state of the Indian Air Force’s combat aircraft fleet, which has reached an unprecedented low. The IAF is currently operating with just 31 squadrons, a number not seen since the 1965 India-Pakistan war.

The authorized strength for the IAF is set at 42 squadrons, a target intended to reflect the strategic threat levels at India’s borders. However, the force has been steadily shrinking due to the retirement of aging Soviet-era aircraft, with replacements failing to be inducted at a pace necessary to maintain operational readiness.

Compounding this challenge is the IAF’s ongoing struggle with the Medium Multi-role Combat Aircraft (MMRCA) acquisition process. India’s request for information (RFI) to acquire 114 fighters has yet to make significant progress, further delaying the replenishment of its fleet.

Meanwhile, India’s adversaries, such as China and Pakistan, continue to develop or acquire advanced fighter technology. China now operates two stealth fighter jets, while Pakistan is in the process of acquiring J-35 stealth aircraft from China.

With the slow pace of domestic development and the mounting need for advanced aircraft, joining the UK-led sixth-generation program could become an increasingly attractive alternative for India.

However, Patel pointed out that there is a possibility that GCAP’s final design may not align with India’s specific aviation needs, which could be better addressed by adapting and advancing the indigenous AMCA program in the coming years.

He noted, “Mostly, it is admitted by seeing the pace and innovation of private startups that the domestic defense industry of India will stand shoulder to shoulder with the timeline of GCAP. If India achieves early development of superior engines like the Japanese XF9-1, Russian Saturn Izdeliye 30, and Chinese WS-15, the possibility of India joining GCAP will be minimized significantly.”